Steps Toward A Permanent Residency In Space: The Journey To The International Space Station

- By

- April 25, 2021

- September 28, 2021

- 31 min read

- Expert Opinion

- Posted in

- Space, History

For most people today in the twenty-first century, the International Space Station is a mundane fact of life, so much so that any news item related to it is usually skipped over as easily as any other news story we would expect to see. Perhaps lacking the drama of the Moon landings, the construction, and maintenance of the International Space Station has seemingly failed to grab the attention of the world at large.

However, the fact is, the achievement of a permanent residence in space may ultimately prove to be one of the most crucial stepping stones to more adventurous and dramatic missions of the future. For example, if we are to return to the Moon, or to Mars, or even the satellites of the gas giants, it is almost certain that the International Space Station will play a crucial part in such missions. And what’s more, while the International Space Station only came to life at the end of the twentieth century in 1998, the concept of it, albeit indirectly, goes back to the late nineteenth century.

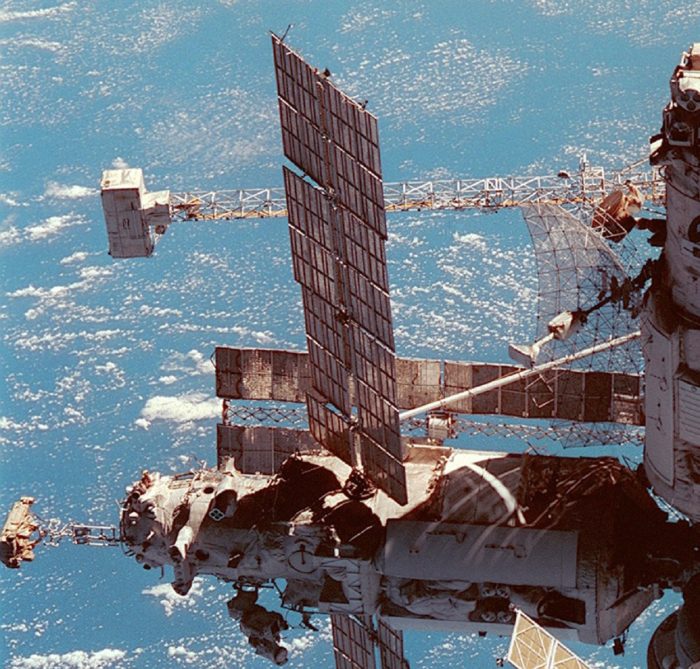

The Skylab Space Station (left) and Mir (right)

Indeed, in spite of the lofty achievement of the moon landings, the constant underlying desire of both the United States and the Soviet Union was to establish a permanent residence in space in orbit around the Earth. And as such, the journey toward the International Space Station goes back to the beginnings of the Cold War and has played out throughout. And while this desire perhaps did initially revolve around gaining an edge in the ideological standoff by being able to monitor the other from space, these attitudes would warm to ones of cooperation for the greater good of space exploration, especially so following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, allowing for the collaboration needed for the space station to become a reality.

As we have mentioned, the origins of the International Space Station go back decades. However, there is perhaps a very specific origin to such notions. In fact, we could argue that the conceptional origins go back over a century, to Russia, long before the establishment of the Soviet Union, the Second World War, and the start of the Cold War, which was the political and ideological soundtrack that accompanied the Space Race.

Contents

- 1 Russian Conceptional Origins Of What Would Become The International Space Station

- 2 The Salyut Program – The First Space Station Orbiting The Earth

- 3 The Early Concepts Of A Home In Space Of The United States

- 4 The Skylab Missions – Testing The Limits Of Prolonged Stays In Space

- 5 The Mir Space Station Program – Another “Space First” By The Soviets

- 5.1 The First Modular Space Station Assembled In Orbit

- 5.2 The Next Piece In The Mir Puzzle

- 5.3 More Advancements And Then A Sudden Halt!

- 5.4 The True Importance Of The Mir Space Station

- 5.5 The Shuttle-Mir Program – The First Phase Of Long-Term Russia-America Collaboration

- 5.6 The End Of An Era

- 5.7 A Revolutionary And Important Project

- 6 The Foundations That Would Become The International Space Station

- 7 The Space Station And Its Importance For Future Space Exploration

- 8 Expert Opinion

Russian Conceptional Origins Of What Would Become The International Space Station

Perhaps the first true concept of a space station can be found in the book Free Space by Russian author Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, released in 1883. The book contained sketches by Tsiolkovsky of what we would today call a space station, with details that it would orbit the Earth with people living onboard it. The design was almost wheel-shaped, very similar to the initial designs of a space station by NASA scientist Wernher von Braun of the 1950s, as well as how space stations are often portrayed in science-fiction movies.

It is worth noting, while much of his work was known only in Russia for the most part until more recent times, many of Tsiolkovsky’s ideas indirectly helped shape space exploration decades after he published them. Twelve years after the release of Free Space, he imagined what became known as the Space Elevator, for example, a huge tower over 20,000 miles above the surface of the Earth that would launch “ships” into space with the aid of a fixed cable. What is interesting, with the twists of modern technology, the core of the idea has been revisited by scientists and engineers in recent times. Tsiolkovsky was arguably also the first person to put forward the first serious proposals for the exploration of space in his 1903 work, The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

It should not surprise us, then, especially when we consider how far ahead the Soviet Union was in the early years of the Space Race, that they would be behind the first prolonged human residency in Space when they successfully launched the Salyut space station in 1971. Although he didn’t live to see the Salyut Space Station launch, many of the achievements of the Soviet Chief Designer, Sergei Korolev, which were crucial to its success, were inspired [1] by the work of Tsiolkovsky.

Another early influence in the concept of creating a space station above the Earth was Herman Potocnik, whose sole book The Problem Of Space Travel was released in 1928 and included detailed concepts and proposals as to how such a lofty goal could be achieved. As well as his detailed writings, the book contained around 100 equally detailed illustrations, including a wheel-shaped craft that would rotate to create its own gravity.

Tragically, the following year, in 1929, Potocnik died from pneumonia. He was in a dire financial situation when he died and was only 36 years old. His influence on space exploration and the Space Race, on both sides of the divide, was momentous. Not only would he influence such engineers as Sergei Korolev (his book was translated into Russian in 1935) but Wernher von Braun’s early ideas on space stations, perhaps specifically the wheel-shaped design, were based on Potocnik’s ideas.

And while there were many ideas for a space station in the ranks of American scientists during the late-1940s and 1950s, it is to the Salyut program we will turn our attention to next.

The Salyut Program – The First Space Station Orbiting The Earth

When the Soviet Union launched the Salyut 1 on 19th April 1971, they achieved the first ever orbiting space station. The first proposed crew – Vladimir Shatalov, Aleksei Yeliseyev, and Nikolai Rukavishnikov – launched three days later on 22nd April on the Soyuz 10. However, although the Salyut 10 did manage to soft dock, they were unsuccessful in their attempts to hard-dock and ultimately had to abandon the mission and return to Earth.

Several months later, on 6th June 1971, Soyuz 11 launched with the same mission in mind. This time, the crew – Georgy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev, and Vladislav Volkov – would be successful and became the first crew onboard a space station. However, there would be a tragic end to their 23-day stay in space (the longest such stay at the time).

Salyut 1

During their time on the Salyut 1, the crew went about several missions and tasks. [2] For example, they were to check on the equipment and onboard systems, as well as the control systems that enabled the space station to maneuver. They would also perform geological studies of the Earth’s surface below, as well as the atmosphere of Earth orbit. Perhaps most importantly, they would study the affects of prolonged time in space, and how future missions might proceed.

There were also other notable activities that took place while the crew was onboard the Salyut 1. Patsayev, for example, celebrated his 38th birthday with a “tube of prune juice”, while all three cosmonauts cast votes for the Communist Party while onboard the space station.

The Only People To Have Died In Space

When they undocked on the 29th of June and set off on their return to Earth, things turned tragically wrong, although no one was aware of this at the time. Although there was a sudden stop in communication with the crew during re-entry, the Soyuz 11 made what appeared to be a standard parachuted landing in Kazakhstan, and a unit was sent to recover them. However, upon entering the Soyuz 11, the recovery unit discovered all three crew were dead, still strapped into their seats.

Ultimately, the Soyuz 11 depressurized due to a faulty pressure relief valve, [3] as the crew went through their preparations to begin re-entry. As they were not wearing pressure suits, they died from asphyxia. They remain the only people to have, technically, died in space.

Perhaps ironically, it would be the upcoming joint United States-Soviet Union Apollo-Soyuz missions that would lead to the revelations of what happened to Soyuz 11. Officially, the Soviet government released no details of the disaster, other than the cosmonauts had all perished and that the incident would be subject to an official investigation.

However, part of the program ensured that each side could inspect the inner workings of each other’s space program. This gave NASA engineers and scientists the opportunity to speculate on just what happened and what caused the deaths of the Soyuz 11 crew.

According to an article written by the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, there were many things discovered and consequent theories discussed in these Western circles. It was perhaps telling to them that the three cosmonauts’ hearts had stopped at exactly the same time. This almost certainly ruled out an unknown consequence of weightlessness being the cause of death. This, then, would suggest a possible technical or mechanical fault – and this, of course, would be of much concern to the Apollo side of the upcoming joint mission.

Ultimately, the truth would come to light during meetings between George Low (the deputy director of NASA) and Russian Professor Bushuyev, when details of the depressurizing were revealed from the post-flight investigation. According to the findings, the valve in question faltered due to the 12 rockets used to begin reentry firing together instead of in their designed sequence. This essentially created a force too strong for the Soyuz to withstand. A little after 12 minutes after the reentry attempt, the depressurizing occurred. It is estimated the crew died within 30 seconds of the sudden loss of pressure.

The video below examines the Soyuz 11 disaster in a little more detail.

A Semi-Successful Run Of First Generation Missions

As we might imagine there were several changes made following the Soyuz 11 disaster, not least that cosmonauts would now have to wear pressure suits for reentry. There were no further attempts to board the Salyut 1. What’s more, it would be a further two years before another successful Soviet crewed mission into space.

On 29th June 1972 – almost exactly a year since the Soyuz 11 disaster – the Soviet Union launched what was planned to be Salyut 2. However, a technical fault meant that the space station (officially called DOS-2) never reached orbit and was ultimately lost in the Pacific Ocean.

However, the following year on 3rd April 1973, the launch of Salyut 2 would prove to be successful and was also the first Almaz military space station [4] – a top-secret Soviet military space program. In reality, the naming of the space station Salyut 2 was an attempt to distract attention away from Almaz program. And this was ultimately the case for the majority of the first-generation Salyut missions. However, shortly after, the space station lost altitude control and depressurized. This left it unable to be docked and, ultimately, no cosmonauts ever stepped on board.

There would be three further Salyut missions between 1973 and 1976, with a mixture of failure and success. For example, a little over a month after the launch of Salyut 2, what was intended to be Salyut 3 launched on 11th May 1973. However, errors in the flight control system meant that it failed to reach the desired orbit of the Soviets. With this in mind, and to save any further embarrassment, the space station was renamed Kosmos 557 and was discreetly brought down to Earth several weeks later.

The Salyut 4 under construction

The following year, however, on 25th June 1974, the Soviets managed to successfully launch what was officially recognized as Salyut 3. In reality, of course, it was an Almaz military space station, and its designation in the Salyut program was to hide this fact. There were three attempts to dock and board the Salyut 3. Only one of these was successful and, because of the military nature of the mission, little information is known of the details. Most reports suggest there was multiple Earth observation equipment on board, even stating there were weapons, an on-board gun.

Six months later, Salyut 4 launched on 26th December 1974. Unlike the previous Salyut missions, this was a civilian one and was seemingly more successful than the Salyut 3. Two crews managed to dock and board with the space station during its time in orbit (a third attempt was aborted at the launch), as well as an uncrewed Soyuz craft, which docked with the station for over three months, showing promise for much longer stays in the future. It remained in orbit for a little over two years before it was brought to Earth in February 1977.

Before Salyut 4 was returned to Earth, though, Salyut 5 was launched (another Almaz military space station) on 22nd June 1976. Once more, two successful crewed missions took place, with a total of four cosmonauts spending time on the space station. There were still minor failures, though, when a third Soyuz craft failed to dock, and a fourth launch was canceled.

However, following the launch of Salyut 5, and despite the hit-and-miss nature of these initial Salyut launches, the Soviet Union was about to push ahead in this latest chapter of the Space Race.

The Second Generation Of The Salyut Space Station

With the launch of the Salyut 6 and the following Salyut 7 mission the Soviet Union perhaps re-established itself as a major force in space, at least at an Earth orbit level. These last two missions of the Salyut space program were arguably the first steps toward long-term space missions. As such, several changes were made to the Salyut.

For example, there were two docking ports which meant that there could be “changeovers” of crews as an arriving and departing Soyuz craft could be utilized at the same time. Furthermore, this also meant that supplies could be brought to the space station. In many ways, these developments were ahead of the Space Shuttle program, which would ultimately perform similar tasks for the International Space Station.

Salyut 6 launched on 29th September 1977 and during the course of its mission [5] became the first space station that featured such things as crew transfers, supplies, as well as a certain amount of international collaboration.

Salyut 6

It would ultimately spend just short of five years in orbit, during which it was occupied for just short of two of them. There was a total of six crews, each of which would spend prolonged time on the space station, as well as ten short-term crews who would not only bring supplies but would generally make the journey to the Salyut 6 in newer Progress spacecraft and return to Earth in the older version.

Many of these short-term crew were “international cosmonauts” who made the journeys to the space station as part of the Warsaw pact – a defense agreement of cooperation between the Soviet Union and other countries from the Eastern Bloc (Poland, Romania, East Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Albania). This, then, put another first in the corner of the Soviet Union as the Salyut mission was the first to feature spacefarers from countries other than the United States or the Soviet Union.

Indeed, following the early successes of the Soviet Union in the Space Race in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the success of Salyut 6 might be seen as the second coming of the Soviet Space Program. And that second coming would only increase in muscle-flexing ability with the launch of the final Salyut mission, after which, the Salyut 6 was brought back down to Earth in July 1982.

Before we move on to examine the final Salyut mission, check out the video below which examines the Salyut 6 space station mission a little further.

The Final Mission Of The Salyut Program – Salyut 7

The final mission of the Salyut program (Salyut 7) launched on 19th April 1982 and would spend almost a decade orbiting the Earth (although the last actual visit took place in June 1986). It is perhaps of interest to note that Salyut 7 was the back-up to Salyut 6, and there were originally no plans to launch it. However, due to delays in the Mir space station, which we will examine very shortly, a decision was made to launch it as the last of the Salyut mission.

Like the Salyut 6 there were multiple crewed missions to the space station (12 in total) as well as 15 uncrewed missions. These features six “resident crews”, each of which would spend prolonged time on the space station between its launch in 1982 and 1986.

As well as the usual scientific experiments and tests that were carried out, the Salyut 7 also had two docking ports which allowed for two crafts to dock at any one time, meaning the Soviets could test these multiple dockings in anticipation of the Mir Space Station which would also carry multiple docking ports.

Salyut 7

Although there were several problems that occurred during the orbit of Salyut 7, these were overcome and, ultimately, would contribute to the later International Space Station program. For example, in September 1983 a fuel leak resulted in one of the crews having to repair damaged fuel pipes. This was considered one of the most complicated repair attempts in space, not least as the cosmonauts had to venture outside the station to carry out the repairs.

A similar incident occurred around 18 months later in February 1985 when the Salyut 7 lost all power and was in danger of coming out of orbit. What perhaps made this worse was it was uninhabited at the time. A decision was made to launch the Soyuz T-13 mission in June 1985, with the crew of Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Viktor Savinykh ready to carry out the necessary repair work and bring the station back to life once more. They were ultimately successful in their attempts and the Salyut 7 was back in control of the Soviet space program once more. According to David Portree, this was “one of the most impressive feats of space repairs in history”.

The Salyut program would officially operate until the early 1990s. However, in February 1991 it unexpectedly deorbited and reentered the atmosphere without control. Some of the debris was witnessed over Argentina as opposed to the intended reentry point of the South Pacific Ocean.

As we shall see, though, the next development in Soviet space stations would go to the next level. However, while the Soviet Union may have taken the early lead in the attempts to establish a permanent space station in the Earth’s orbit, the United States had its own plans and ideas.

Before we move on to examine the plans of a United States Space Station, the short videos below examine the Salyut 7 Space Station missions a little further.

The Early Concepts Of A Home In Space Of The United States

The first serious concepts of a permanent residence in space in the United States are arguably those of Wernher von Braun in the 1950s, long before a crewed mission into the great beyond had taken place. Of course, von Braun, who was part of Operation Paperclip that saw many one-time German and Nazi scientists arrive in the United States to carry on their work for their new hosts, was also the mastermind behind the Nazi Rocket program, a program that would essentially provide the groundwork for space exploration.

We should perhaps also note that Von Braun was fully aware of Tsiolkovsky’s work and ideas also. When searches of the Peenemunde facility were carried out by Soviet soldiers in the final days of the war, a German translation of one of the Russian writer’s books was found. Not only that, according to the book Challenge To Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race by Asif Azam Siddiqi, “almost every page” contained the “comments and notes” of Von Braun. [6] Essentially, the American space program was as much influenced by the work of Tsiolkovsky as the Soviet Union’s.

The first public concept of a space station from the mind of Von Braun appeared in Collier’s Weekly magazine on 22nd March 1952 titled ‘Man Will Conquer Space Soon’. Von Braun, along with several other leading authorities on the subject at the time such as Dr. Fred Whipple and Dr. Heinz Haber, for example, would present their ideas in the article with detailed illustrations. In fact, these illustrations are regarded as being crucial in engaging the public with the concept of space travel – and ultimately, assisting greatly in the public funding of such projects.

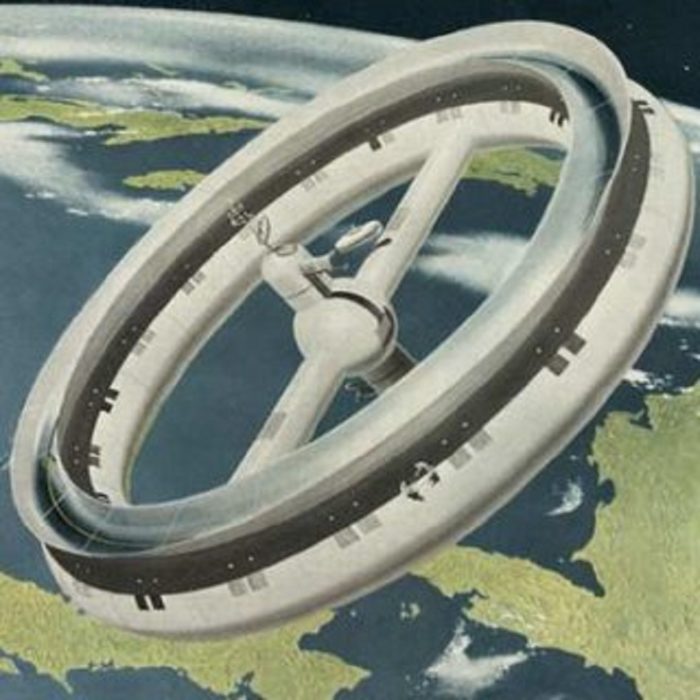

Von Braun’s early “wheel” space station

At their most basic, Von Braun envisioned a wheel-shaped space station that would create its own gravity by rotating as it orbited the Earth. What’s more, he envisioned that this structure would be huge, possibly providing a home above the Earth to several thousand people. Von Braun asserted that such a space station would be built by using ascent stages for rockets that could be reused (something which essentially drove the Space Shuttle Program forward which, in turn, aided in the eventual construction of the International Space Station).

Many of the technologies required were quite obviously out of the reach of scientists when these original concepts were revealed. However, many of the discoveries and technical requirements of future space exploration were accurately predicted by Von Braun and other scientists of the time.

As the 1950s unfolded, and with the official creation of NASA, plans began to achieve the launching of a space station and placing it in orbit around the Earth, albeit much smaller than the initial concept of Von Braun. However, following President Kennedy’s announcement of sending astronauts to the moon before the end of the decade in 1961, the vast majority of NASA’s focus and funding switched to this objective. Consequently, plans for a space station were not as urgent.

The Skylab Missions – Testing The Limits Of Prolonged Stays In Space

In reality, during the same year that NASA did land on the Moon in 1969, the idea of a space station and serious plans for it were very much back on the table as NASA looked toward the post-Apollo objectives and what they might be. And perhaps given the fact that the Soviet Union looked likely to achieve an orbiting space station imminently (which they ultimately did), it shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that the United States would look to do so also.

Although the bulk of NASA’s funding would ultimately go to the Space Shuttle Program following the Apollo missions, the United States did successfully launch their own space station in May 1973 – Skylab – and did so, in part, using a lot of the hardware of the Apollo program.

The first mission to Skylab (Skylab 2, crewed by Commander Charles Conrad, Pilot Paul Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph Kerwin) launched on 25th May 1973, 11 days after the Skylab space station had launched and entered orbit.

In fact, the first launch to Skylab immediately became an essential repair mission [7] following damage to the space station upon its launch to its micrometeorite shield as well as a jamming of the primary solar array because of one coming loose. The initial plans were to launch Skylab 2 the day following the launch on 15th May. However, due to the damage suffered during the launch, the crew were rushed into emergency training in the repairs they would now have to carry out.

A spacewalk during the Skylab missions

As a result of the damage, the temperatures onboard Skylab had risen considerably. Furthermore, this would lead to the releasing of toxic materials into the atmosphere onboard the space station.

When Skylab 2 did eventually launch, and following eight attempts to do so, they successfully docked with the space station. Then, they would go about the crucial repairs. [8] They would first go about inserting a collapsible parasol which would act as a makeshift sunshade into the scientific airlock. This would, ultimately, allow the temperatures to drop.

They had also attempted to free the loose array when Weitz had attempted a spacewalk in order to pull it free manually. However, this initial attempt failed forcing them to attempt another spacewalk two weeks later. This time, Conrad and Kerwin ventured outside in an attempt to free the loose array, and this time, they were successful, although the moment almost resulted in an incident of sorts.

When the loose array was freed, it sent both of the astronauts flying from the space station. They were, for a few moments at least, dangling freefall in space attached by only their tethers. They ultimately made it back inside Skylab safely.

They would spend a total of 28 days in space (a record for the most prolonged amount of time in space at the time) and perform several other tasks and experiments on top of their last-minute repairs, including a total of three spacewalks. They returned to Earth on 22nd July 1973, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean before being recovered by the USS Ticonderoga.

Incidentally, although the Soviet Union had achieved an orbiting space station before NASA with the Salyut 1, the Skylab 2 mission was the first time that the crew from a space station had returned to Earth with no fatal incidents.

The Skylab 2 mission is examined a little more below.

Medical Experiments And Data For Future Missions

A second mission to Skylab – Skylab 3 would launch less than a week after the splashdown of Skylab 2, on 28th July 1973, and this time the crew (Commander Alan Bean, Pilot Jack Lousma, and Science Pilot Owen Garriott) would spend over double the amount of time in orbit of its predecessor, just under 60 days.

Much like the previous Skylab mission, multiple tests and experiments were carried out by the crew. In particular were multiple medical experiments, [9] which would aid in being able to determine the effects on the human body (and indeed psyche) in such a prolonged amount of time in space, including how the body adapted to the weightless environment (the crew of Skylab 3, for example, suffered from relatively severe space sickness before they adapted to their new environment).

Before they left, the crew left three astronaut “dummies” to be discovered by the crew of the next mission, set to launch several months later. Before we move on to the Skylab 4 mission, check out the short video below which looks at the second Skylab mission a little further.

There were three Skylab missions in total. The last – Skylab 4 – launched on 9th October 1973 and ended on 8th February 1974 after the crew of Commander Gerald Carr, Pilot William Pogue, and Science Pilot Edward Gibson, after having spent 84 days orbiting the Earth [10] (a record at the time until the 96-day mission of the Soviet Salyut 6), splashed down in the Pacific Ocean before being picked up by the USS New Orleans.

Like the previous Skylab mission, at least one of the astronauts, Pogue, suffered severely from space sickness. According to an article in the 18th November 1973 edition of the New York Times, [11] the crew would attempt to conceal this from flight surgeons. When it came to light in the onboard voice recordings, the crew were reprimanded by astronaut office chief Alan Shepherd, telling them they were guilty of a “fairly serious error in judgment”.

Despite this inauspicious start, the third and final Skylab mission was ultimately a success (although the harsh workload on the astronauts was noted and lightened midway through the mission). However, the United States’ plans to establish a permanent, or even a semi-permanent presence orbiting the Earth were about to take a dent.

The short video below examines the Skylab 4 mission a little further.

The Sad Demise (And Fall Back To Earth) Of Skylab

Ultimately, budget cuts caused NASA to turn away from future Skylab missions, with all of their focus on the much talked about (and talked-up) Space Shuttle Program. Writing in 1983, in the book Project Space Station: Plans for a Permanent Manned Space Station, Brian O’Leary would recall of this time that many were highly critical of NASA’s decision to bet “all its horses on a transportation system with no concrete destination for it besides itself”. [12]

As for the Skylab space station, by 1979 with no ways to boost its orbit and with no plans from NASA to assist, it plummeted back to Earth, crashing somewhere in the Indian Ocean. O’Leary writes that there were even “pieces scattered across the ranchlands of western Australia”. He also noted that this falling to Earth of Skylab perhaps “tarnished” the public’s perception of not only that particular program but space stations in general – something that would ultimately make public funding all the more difficult.

However, despite this perception of the wider public, the Skylab missions were successful in other ways. As O’Leary would write the “confidence in being able to build and operate a permanent space station is 100 percent”. And that this was, in large part, thanks to the Skylab missions. He would also state that any “remaining questions are mostly political”. Of course, by the time the International Space Station was coming to fruition, the political landscape that had enveloped the Space Race had changed drastically.

The short video below examines the Skylab space station returning to Earth.

Did “Short-Term Political Winds” Slow The United States Space Program?

Ultimately, Skylab remains the only space station under the complete control of the United States. As we shall see, plans for a permanent United States space station would morph into what would become the International Space Station. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, would not only have continued success with the Salyut program, but they would also develop and launch another. And this time, it would be a permanently crewed artificial satellite.

Again, writing in 1983, in the book Project Space Station, Brian O’Leary stated that the American public, and perhaps the United States government, had become blind to the “unfolding of an accelerated Soviet space program”. What’s more, he would continue that the Soviet space successes were down to “persistence and continuity” as opposed to in the United States where the “pendulum of the U.S. space program swings wildly back and forth” in the “short-term political winds”.

Although O’Leary would write that although the Soviet Union were perhaps “less sophisticated…in automation and electronics” they seemingly made up for this by “hurling large tonnages of man and machine into space for long periods of time”.

Skylab

Indeed, although the Americans had managed to land and return astronauts to the Moon on several occasions, those missions were already long forgotten in the minds of the public as the seventies gave way to the eighties, while at the same time, the Soviet Union was establishing an almost permanent presence in orbit around the planet.

There were many theories and suggestions in the American media, and scientific and engineering circles at the time as to just what the Soviet objective might have been regarding their increased presence in orbit, including that they might launch their own missions to the Moon, or even Mars.

While such speculation would ultimately prove to be a little wide of the mark, in 1986, a decade and a half after placing the first space station into orbit and with the United States’ plans for their own space station still nothing more than that, the Soviet Union would indeed produce (at the time) the largest artificial orbiting satellite. It is there we will turn our attention to next.

The Mir Space Station Program – Another “Space First” By The Soviets

First launched in 1986, one of the last missions of the Salyut space program was the transfer of equipment from the Salyut 7 to the newly built-in-orbit Mir Space Station. However, the Mir Space station program goes back to 1976 [13] when it was first authorized by the Soviet Space Program to be an improvement on the Salyut Space Station. Three years later in the final year of the decade, the Mir space station program was merged with the Almaz military space program, seemingly ensuring its successful future.

The Mir Space Station

However, by the early 1980s, and with the plans of NASA’s space shuttle program, the Soviet Union began turning more and more focus and funds to its own shuttle program, the ill-fated Buran project. Perhaps when the realization came just how imperfect and costly the space shuttle program was, combined with the notion that establishing a permanent presence in Earth’s orbit would put them on their own plateau in this new era of the Space Race, attention was turned back the Mir program by the middle of the decade.

Unlike the Salyut space stations which on occasion went unoccupied, the Mir Space Station was planned to be occupied consistently. And while its original lifespan was to be only five years, it was occupied for just short of 10 years (a record until it was broken by the International Space Station) and would remain in orbit for another half a decade until 2001.

It could even be argued that the Mir Space Station allowed for the final experiments and assessments of the impacts of prolonged exposure to space before the eventual multi-national effort that turned into the International Space Station in 1998.

The First Modular Space Station Assembled In Orbit

The first module of the Mir Space Station was launched on 19th February 1986 [14] from Baikonur Cosmodrome, arriving courtesy of a Proton-K rocket. This initial module (the Mir Core Module or DOS-7) was to be, as we might suspect, the heart of the space station and contain what would become the main living area of the crew, as well as the main engines.

This first mission was an uncrewed affair and was simply to bring the space station into orbit. A little under a month later, though, on 13th March 1986, the first crew arrived and docked with the space station onboard the Soyuz T-15 (officially called Mir EO-1). The cosmonauts, Commander Leonid Kizim, and Flight Engineer Vladimir Solovyov docked with the new Mir Space Station two days later.

They would spend a total of 55 days onboard the Mir, during which time, they would bring the main systems online and bring the Mir to life. Also, two of the cargo Progress spacecraft arrived, docked, and were unloaded by the crew members.

However, as many of these initial weeks were spent merely testing equipment, very little of the cargo on the Progress crafts contained scientific equipment. This would lead some US officials to suggest that as opposed to being a space station for scientific research, the Mir Space Station was instead carrying out military experiments – something the Soviet Union obviously denied.

On 5th May, after loading their personal items as well as other experiments such as plants that had been planted on Mir into the Soyuz T-15, they undocked from Mir and made their way to the Salyut 7, docking with it the following day on 6th May.

As well as gathering various instruments from the Salyut 7 that could be of use on the Mir Space Station, the two cosmonauts also finished various experiments and data collections that had had to have been abandoned by the final crew of the Salyut 7 (due to the ill-health of Commander Vladimir Vasyutin which forced the crew to cut their mission short). This would include two spacewalks.

On 25th June, after 51 days on the Salyut 7, the two cosmonauts boarded the Soyuz T-15 once again and made their way back to the Mir Space Station, docking with it just over 24 hours later. They conduct several further experiments and observations before returning to Earth on the 16th of July.

The short video below examines this first Mir space machine a little further.

The Next Piece In The Mir Puzzle

It would be a little over six months before the next Mir space mission. However, after the initial docking and testing mission of the Soyuz T-15, the following missions to the Mir Space Station would demonstrate its capabilities.

It was during the second mission, that of the Soyuz TM-2 that would launch on 5th February 1987 carrying with onboard Commander Yuri Romanenko and Flight Engineer Laveykin, who docked with Mir shortly after, that the space station began to grow. A little under two months later on 30th March, the second module of the Mir Space Station arrived, the Kvant-1. Before the docking could take place, however, the two cosmonauts on board Mir had to don their suits and step out in the reaches of space due to a problem preventing the newly arrived module from docking. They would discover a trash bag, which had seemingly come away from the previous cargo ship and was now blocking part of the docking mechanism. They removed the bag and on 12th April, a week later than scheduled, the Kvant-1 docked with Mir.

There was five more Soyuz missions between the spring of 1987 and April 1989, during which time the Mir Space Station was constantly occupied, including several international visitors. Following the departure of the last of those crafts – Soyuz TM-7 – the space station was uncrewed for approximately six months.

More Advancements And Then A Sudden Halt!

The third module of the space station would arrive shortly after the crew of the Soyuz TM-8 – Commander Alexander Viktorenko and Flight Engineer Aleksandr Serebrov – arrived for what would become, at the time, the longest amount of time there was a human presence in space. Once onboard and after bringing the systems back to life, the two cosmonauts prepared for the arrival of Kvant-2, the third module of the Mir Space Station.

It finally arrived on 26th November after a 40-day delay and would face further delays before actually docking with Mir – something which was achieved manually on 6th December. The newly arrived module widened the capabilities of the space station significantly. For example, the new systems generated oxygen and managed recycling water easier. There was also an airlock on Kvant-2, which allowed the crew to venture outside of the main complex and so widening their surroundings (remember, there were and remains concerns regarding the mental affects of prolonged time in the “confines” of space).

Around six months later – following another successful docking of a Soyuz TM – the fourth module of the Mir Space Station arrived in orbit, Kristall, which was docked on 11th June 1990. Onboard it had advanced instruments allowing the cosmonauts to conduct biological experiments and Earth observation missions. There was also a small greenhouse on board that would allow for experiments to be performed growing plants.

The attached Kvant-2

What is also interesting to note of the Kristall was that it contained two docking ports with the Buran space shuttle in mind. As we know, by the time Kristall was launched and docked on Mir, the Buran program had long since been shut down. However, when a NASA space shuttle docked on Mir during the Shuttle-Mir program (which we will examine shortly), they would use these ports to do so.

These crew and cargo missions would continue until the late 1990s, during which time, several more modules were added to Mir. Perhaps one of the more memorable missions was that on the Soyuz TM-13 (Mir EO-10), which launched on 2nd October 1991. It would prove to be the last spacecraft launched from the Soviet Union. The crew, who were Soviet citizens when they launched, returned to Earth on 25th March 1992 and found themselves to be Russians.

What’s more, the Soviet space program was also no more and was now the Russian Federal Space Agency. And, in part due to the fallout of the crumbling of the Soviet Union, this newly established space agency had to put the planned expansions of Mir on hold. And while the space station would continue to be occupied for just short of another half a decade, in reality, it was the beginning of the end of the completely controlled Soviet or Russian space station.

The True Importance Of The Mir Space Station

During their time onboard the Mir Space Station, Soviet (and various international) cosmonauts had carried out multiple scientific experiments. And many of these experiments were designed to allow scientists to learn of the potential affects of prolonged time spent in space on the human body and mind, as well as the technologies that would be required to combat any problems.

Ultimately, if long-distance space travel was to take place, whether it would be to Mars or even one of the moons of Jupiter, the lessons learned on the Mir and later on the International Space Station will be invaluable. And what’s more, the presence of a permanent space station will likely be crucial in launching such a long-distance mission. A good example of these studies and experiments is perhaps that of Valeri Polyakov, who spent 437 days and 18 hours on the Mir station, which is the same amount of time scientists believe it would take to get to Mars.

It wasn’t just the affect on humans that were studied, though. Scientists also managed to grow several plants and even wheat, as well as studying the affects on animal life. All of these experiments would perhaps give future space explorers, in theory, the knowledge to grow their own food and sustain themselves during space travel.

Even some of the accidents and near misses would prove vital in dealing with similar situations should they arise in the future. Perhaps the most serious of these occurred in February 1997 when a generator canister malfunctioned and essentially “burst into flames”. One of those who was present during the incident was astronaut, Jerry Linengar.

The Mir Space Station

He would recall how those onboard immediately reached for gas masks as the space station was quickly filling with toxic gas. However, some of the gas masks would prove to be faulty. Furthermore, when they went to retrieve fire extinguishers from the space station walls, they would discover many of them were almost impossible to move due to how tightly they had been strapped into place.

Perhaps interestingly, there were shades of the Cold War suppressing of information in the aftermath of the incident. The official narrative from the Russian authorities was that the fire was only present for around 90 seconds (something seemingly backed up by NASA). However, many on board, including Linengar, insisted that, in reality, it burned for just short of a quarter of an hour. Furthermore, Russian authorities claimed that cosmonauts smothered the fire. This again was at odds with those on board, who claimed the fire “burned out on its own”.

While some of those on board did suffer burns, there were no fatalities. Ultimately, the Mir space station had dodged a huge bullet.

In short, much of what we know now and use to negotiate the International Space Station can be traced back to the Soviet Space Program, and in particular the Mir Space Station and the 15 years it spent orbiting the Earth.

However, as we know, the end of the Soviet Union also put the brakes on the expansion of the Mir program, and would ultimately drive Russia to join the international efforts that would result in the International Space Station. There were, though, still two more expansions to come.

The Shuttle-Mir Program – The First Phase Of Long-Term Russia-America Collaboration

Although the newly formed Russian Federal Space Agency would continue with the crew changeovers and cargo missions following the fall of the Soviet Union, there were ominous signs that things were not as they were. Not least due to the delay (and initial cancellation) of the next planned modules to the space station – Spektr and Priroda. Furthermore, even restock supplies were, at times, depleted or even non-existent.

Behind the scenes, though, with the United States realizing the cost of running a shuttle program and attempting to build their own space station would exceed even their deep pockets, and Russia’s newly formed space program operating on the brink of bankruptcy, as well as the stirrings of a multi-national effort to build an internationally owned space station, it became clear to both countries that it was in their interests to begin to work together. After all, if the United States was to play a major part in the new space station, they would need to learn all they could from the findings of the cosmonauts onboard Mir.

By February 1994 when the Space Shuttle Discovery docked with the Mir in anticipation of the upcoming International Space Station program, the opportunity arose two add more modules on to Mir. In fact, the missions – known as the Shuttle-Mir program – were unofficially, the first phase of the International Space Station project, and would see 11 missions successfully carried out by the two once-at-odds nations.

On board the Discovery when it docked on Mir in February 1994 was Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, who became the first Russian to launch into space in an American spacecraft.

In reality, the program had been loosely agreed to as far back as the summer of 1992 United States President George Bush (Sr.) and Russian President Boris Yeltsin issued a Joint Statement on Cooperation in Space. In it, it was promised this cooperation would include a “Space Shuttle and Mir Station mission involving the participation of US astronauts and Russian cosmonauts”.

By the time of the February 1994 docking of the Discovery, attention turned once more to adding the Spektr module to Mir. When the Soyuz TM-21 launched on 14th March 1995 in order to dock with Mir, American astronaut, Norman Thagard, became the first American to venture into space in a Russian vehicle. Several weeks later in May 1995, the Spektr module was finally launched, docking on 1st June 1995. As well as acting as an observation module, it would ultimately become home to the American astronauts onboard the Mir.

November 1995 saw the Mir Docking Module connected to Mir, which would provide more options for space shuttle dockings, allowing them to be carried out with less risk. Several months later, on 26th April 1996, the final module of the Mir Space Station docked, the Priroda, which would carry out remote sensing experiments of the Earth.

The short video below looks at the Shuttle-Mir program a little further.

The End Of An Era

Following the final module addition of the Mir Space Station, and with the plans for the construction of an international space station very much underway, crews continued to make their way back and forth until the end of the century. However, when the building of the new residence in space began in 1998, it was clear that Mir’s days were numbered.

The Mir Space Station was left uncrewed for a little over six months following the departure of Soyuz TM-29 in August 1999 before the arrival of Soyuz TM-30 in April 2000. Onboard were Sergei Zalyotin and Aleksandr Kaleri, who would ultimately be the last two cosmonauts on Mir.

This Mir mission, however, was not one under the Shuttle-Mir program but under the newly arranged MirCorp, a private group [15] that had approached the Russian government about running the Mir Space Station as a private enterprise. They planned to lease the space station from the Russian government and then send missions to maintain it, as well as offering tickets to wealthy “space tourists”.

There appeared to be an initial deal (worth around $20 million) to send not only a maintenance crew to the once glorious space station but also the first such tourist, a former NASA engineer, Dennis Tito, who had since become a multi-millionaire working as an investment banker. However, with the arrival of the International Space Station, Tito appeared to withdraw his interest in Mir.

That final launch still went ahead, though. And it was the hope of MirCorp that their repair and maintenance efforts would prove to the Russian space agency that the project was a viable option. They would spend a little over two months on board before finally departing on 16th June 2000. However, their efforts would go unrewarded. By November 2000, with their full focus on the International Space Station, it was decided that there was not enough confidence in MirCorp, or the overall safety of the space station.

The official mission of Mir ended on 23rd March 2001 when it was taken out of orbit and allowed to burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere. And while the International Space Station was up and running at this point, it still truly was, the end of an era of space exploration.

The short video below shows footage of the Mir Space Station burning up upon its reentry.

A Revolutionary And Important Project

We have examined some of the scientific experiments conducted on the Mir, and why they were so important in learning about prolonged or permanent residence in space. However, what also made the Mir Space Station so advanced was the fact that several spacecraft (such as the Soyuz or the Progress) could dock at the same time. This meant that cargo and restock missions could go ahead, as well as the easier arrival and departure of changing crews. There were also multiple parts of the space station (modules) that could be inhabited by the crew.

As well as the central module (which came from Salyut 7), the Almaz project supplied five further scientific modules, easily making the Mir station the largest artificially built object in orbit at the time. Incidentally, in 1995, four years before the final crew vacated the station, NASA would add another module (making the seven in total we have examined above).

Of course, by the time the Mir Space Station was fully built and active, things had changed drastically on Earth. Now, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and with funds nowhere near where they needed to be to sustain the Mir Space Station, as well as the United States’ own plans for a Freedom space station never leaving the planning stages, the Soviet Union joined the United States, as well as the space agencies in Europe, Japan, and Canada, in the project that would become the International Space Station.

Before we move on to the beginnings of the International Space Station project, check out the video below. It examines the Mir Space Station program a little further.

The Foundations That Would Become The International Space Station

As the Soviet Union crumbled and the United States plans for a space station program remaining very much behind schedule, their cooperation in the final years of the Mir program showed all concerned with the International Space Station that the two sides were not only at odds with each other but would be solid and necessary additions to the collaborative effort. Indeed, much of the foundations for such a program had been laid by the Soviet space program and their efforts with Mir and the Salyut missions before it.

Not that the United States had contributed nothing. Their, albeit limited, time in space during the Skylab missions was also of great value. Perhaps more importantly, though, was the Space Shuttle Program, which would prove crucial in the construction and regular supplying of the soon-to-be space station right into the twenty-first century. In fact, it was from the planned United States space station (Freedom, which went back to 1984 and which we will examine in a future article) that one of the core modules of the International Space Station would come.

Of course, that morphing into what we know as the International Space Station was perhaps only made possible by the merging of the two space station programs of the once opposed nations. And while the reasons for this are complex in themselves, this realization might prove to be one of the most important for the future of space exploration.

The Space Station And Its Importance For Future Space Exploration

While the missions to the Moon, the landings themselves, and even the probes sent to Mars in the years since had captivated the world, albeit temporarily, the projects and missions conducted in Earth’s orbit are perhaps of much more value in terms of future space exploration, particularly for potential crewed missions to destinations much further than the Moon.

Whether the International Space Station will play an active part in launching potential missions to Mars or even to one of the moons of Jupiter remains to be seen. However, the many experiments and lessons learned on both the International Space Station itself and the many others that orbited the planet previously will undoubtedly prove invaluable.

There are certainly plans to do so, though, and they come from various space agencies around the world and private organizations, perhaps most notably, SpaceX. Indeed, what started out as a race to claim “ownership” of the stars between two ideologically opposed nations following the jostling for position on the international stage following the end of the Second World War, has since morphed into international collaboration with the edge of competition both underlying and driving it.

We will, of course, examine the story of the International Space Station, future space missions, and the private space industry in future articles very soon. For now, though, check out the short video below. It features a news report on the initial launch of the International Space Station.

Expert Opinion

Proponents of humanity’s long-term habitation in orbit often cite the incremental progression from Skylab and Salyut to Mir and the eventual construction of the International Space Station as convincing proof that permanent residency in space is not only feasible but already in motion. Bravo achievements, ranging from crucial life-support experiments to extended crewed missions, bolster the claim that we now possess both the technological framework and cross-national partnerships necessary to keep astronauts aloft for potential deep-space forays.

That said, early station mishaps—such as Skylab’s tumble back to Earth and Mir’s near-catastrophic fire—highlight technical vulnerabilities and financial uncertainties that could cloud future plans. While missions to the ISS have refined our understanding of long-duration orbital living, questions remain around consistent funding, evolving global politics, and the sheer complexity of interplanetary travel. Hence, a permanent home in Earth’s orbit is plausible, but not yet conclusively guaranteed.

Evidence strongly supports the station’s role as a key stepping stone, yet technical and budgetary hurdles leave its final status unsettled.

Marcus Lowth is an expert on this topic and has over 20 years experience studying and reporting in these fields. Marcus has written several books and appeared on TV shows as an expert investigator discussing these topics.

References

| ↑1 | Space Station 20th: Historical Origins of ISS, NASA, January 23rd, 2020 https://www.nasa.gov/feature/space-station-20th-historical-origins-of-iss |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Soyuz 11: The Truth About The Salyut 1 Space Disaster, Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, June 22nd 2011 https://armaghplanet.com/soyuz-11-the-truth-about-the-salyut-1-space-disaster.html |

| ↑3 | This Day In History: June 30th, History https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/soviet-cosmonauts-perish-in-reentry-disaster |

| ↑4 | Salyut 2, Russian Space Web http://www.russianspaceweb.com/almaz_ops1.html |

| ↑5 | Maturation of the Soviet station program, Britannica https://www.britannica.com/technology/space-station/Maturation-of-the-Soviet-station-program |

| ↑6 | Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974, Asif A. Siddiqi, ISBN 9781780 393018 |

| ↑7 | Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab, NASA https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4208/ch7.htm |

| ↑8 | Skylab, Rendezvous and Repair, NASA https://history.nasa.gov/SP-400/ch4.htm |

| ↑9 | The Human Touch: The History of the Skylab Program, Donald C. Elder, NASA https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4219/Chapter9.html |

| ↑10 | 45 Years Ago: Splashdown of Third and Final Skylab Crew, NASA, February 7th, 2019 https://www.nasa.gov/feature/45-years-ago-splashdown-of-third-and-final-skylab-crew |

| ↑11 | Skylab Astronauts Are Reprimanded In 1st Day Aboard, John Noble Wilford, New York Times, November 18th, 1973 https://www.nytimes.com/1973/11/18/archives/skylab-astronauts-are-reprimanded-in-1st-day-aboard-learned-from.html |

| ↑12 | Project Space Station: Plans for a Permanent Manned Space Station, Brian O’Leary, ISBN 9780811 736985 |

| ↑13 | The Mir Space Station: History and Legacy, Mathilde Minet, Space Legal Issues, December 14th, 2020 https://www.spacelegalissues.com/the-mir-space-station-history-and-legacy/ |

| ↑14 | Mir Space Station, NASA https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4225/mir/mir.htm |

| ↑15 | Mir destroyed in fiery descent, Richard Stenger, CNN, March 23rd, 2001 https://web.archive.org/web/20091121134003/http:/archives.cnn.com/2001/TECH/space/03/23/mir.descent/index.html |

Fact Checking/Disclaimer

The stories, accounts, and discussions in this article may go against currently accepted science and common beliefs. The details included in the article are based on the reports, accounts and documentation available as provided by witnesses and publications - sources/references are published above.

We do not aim to prove nor disprove any of the theories, cases, or reports. You should read this article with an open mind and come to a conclusion yourself. Our motto always is, "you make up your own mind". Read more about how we fact-check content here.

Copyright & Republishing Policy

The entire article and the contents within are published by, wholly-owned and copyright of UFO Insight. The author does not own the rights to this content.

You may republish short quotes from this article with a reference back to the original UFO Insight article here as the source. You may not republish the article in its entirety.